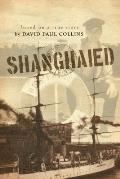

Shanghaied: The

Book

When we meet him, fifteen-year-old Jack Sligo is a boy

preparing to slip away from his Boston Irish home in the wee hours of a 1956 summer

morning. He climbs out a window, leaving behind a sheltering, middleclass

bubble to chase his dream of a glamorous jaunt around the world as deckhand on

a cruise ship.

Sligo does end up on a ship, but, as the title

suggests, not under his own power. After hitchhiking from Boston to Mobile,

Alabama, he is drugged and kidnapped from a seedy sailors´ bar. He awakens the

next day on a ship that has already set sail for South America. Merchant

ships, like prisons, are confined communities of individuals who don´t always

get to choose their own bunkmates or watch mates. Collins leads us deep into a

world where young Sligo learns that for a boat to function, the seamen must

rely on -- if not fully trust -- one another.

Sligo´s sense of race, religion, family, friendship,

work and manhood are all challenged and expanded on the SS Iron Prince whose

crew list reads like a phonebook from Queens, New York: There are Filipinos,

Cayman Islanders, Eastern Europeans, a German, a Norwegian, a Jamaican, a

Brazilian, and a man from the island of Dominica. The boat´s complicated

provenance reflects this diversity and contributes to the plot:

German officers, US owned, flying under a Liberian flag.

Just three months have elapsed when the book ends, but by then Sligo is a young man, with a new, life-altering sense of the world. In between, we, the readers, live a ripping yarn that carries us from Boston to New York to Mobile to Venezuela and back, with a few unexpected stops along the way. Shanghaied reads like a blockbuster movie script, full of scoundrels and heroes, sensitively rendered by this first-time author.

Collins does a number of things very well in Shanghaied. First

among them is his ability to keep an unbroken focus on the first person

narrative of the boy, avoiding any temptation of omniscient narration. This close-in

POV technique ratchets up the story´s dramatic tension. We, the impotent

observers, squirm as we read, unable to protect the boy from the lurking

threats and suspect motives that we see, but the more innocent Sligo cannot.

Another of Collins´ intelligent decisions was to write

short, tight chapters that set a torrid pace. The book´s 72 chapters average

about four-and-a-half pages. Each one ends with forward movement, making it

almost impossible to put the book down.

Despite the rush of the honed plot, there are moments

of poetry. One of my favorites is a beautifully written, existential

conversation that Sligo has with Chips, the ship´s carpenter, about human

existence, religion and God´s presence in their lives. Another, when Sligo goes

on a transcendental bender in fiery bowels of the ship, brings to mind the

famous below-decks blubber-rendering scene in Moby Dick, where Melville strove

to render blubber into poetry.

When I clicked away from the final page (I read the

book on my Kindle), there was a lump in my throat and a knot in my stomach. Not

only did Sligo mature over the course of the book, but so did Collins´ writing in this impressive maiden voyage.

I´m betting there will be a sequel to Shanghaied. If

there is, I look forward to shipping out with Jack Sligo on a new adventure.